From Transformers to Associative Memory, How Titans and MIRAS Rethink Long Context Modeling

What comes after Transformers? Google Research is proposing a new way to give sequence models usable long term memory with Titans and MIRAS, while keeping training parallel and inference close to linear.

Titans is a concrete architecture that adds a deep neural memory to a Transformer style backbone. MIRAS is a general framework that views most modern sequence models as instances of online optimization over an associative memory.

Why Titans and MIRAS?

Standard Transformers use attention over a key value cache. This gives strong in context learning, but cost grows quadratically with context length, so practical context is limited even with FlashAttention and other kernel tricks.

Efficient linear recurrent neural networks and state space models such as Mamba-2 compress the history into a fixed size state, so cost is linear in sequence length. However, this compression loses information in very long sequences, which hurts tasks such as genomic modeling and extreme long context retrieval.

Titans and MIRAS combine these ideas. Attention acts as a precise short term memory on the current window. A separate neural module provides long term memory, learns at test time, and is trained so that its dynamics are parallelizable on accelerators.

Titans, a neural long term memory that learns at test time

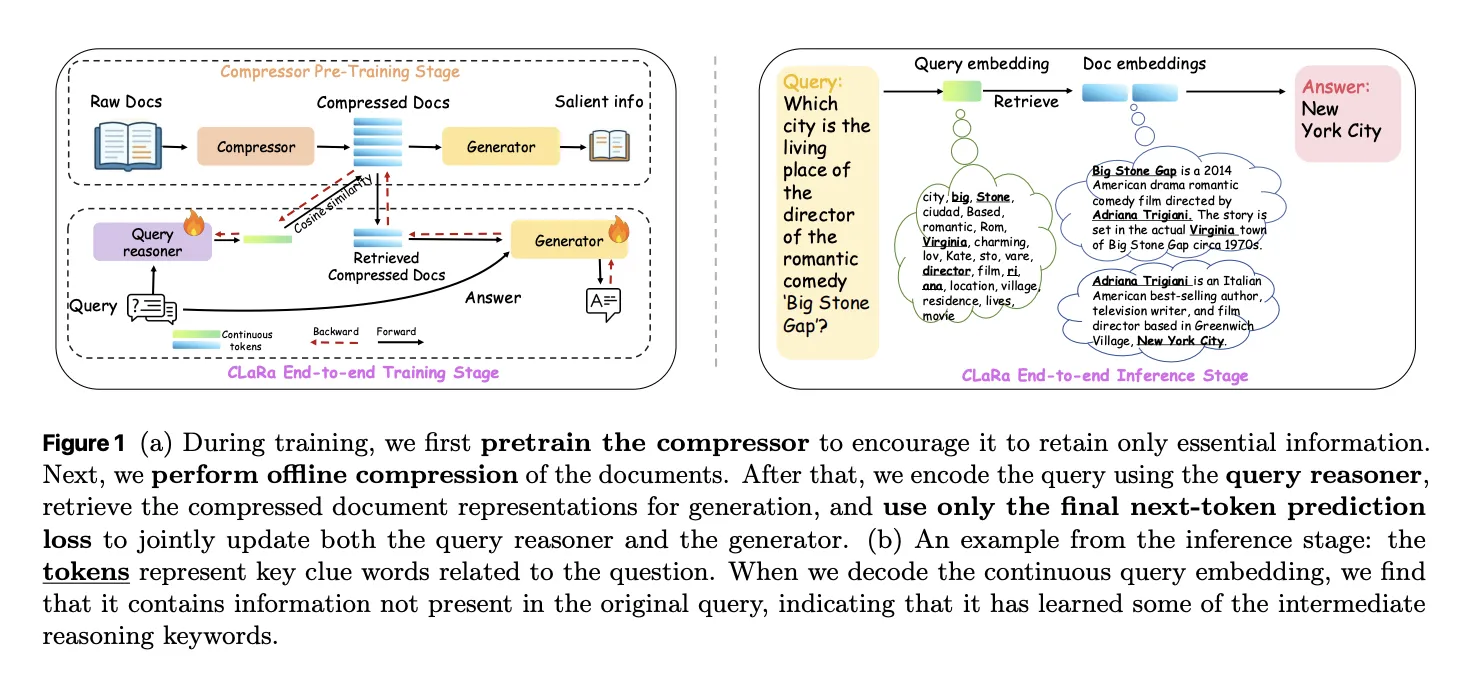

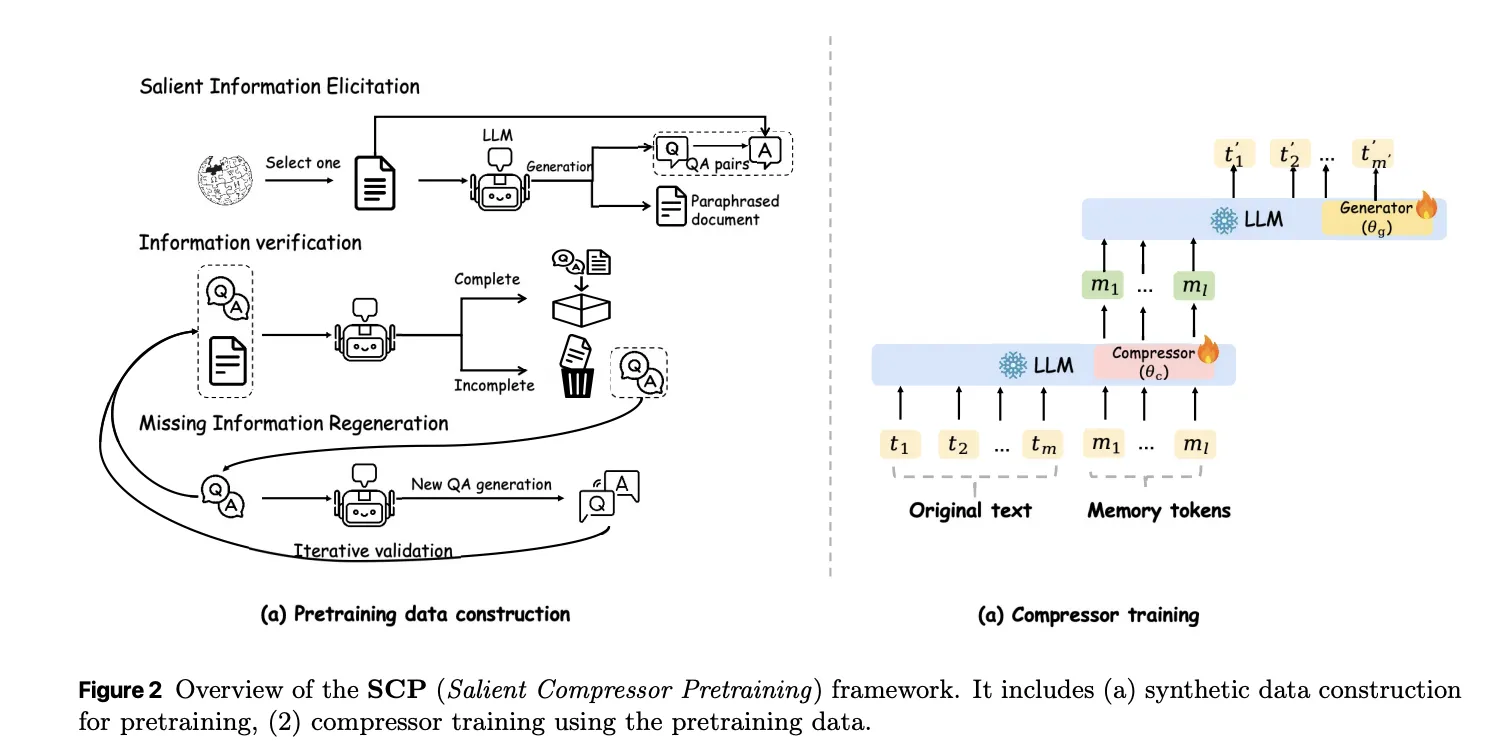

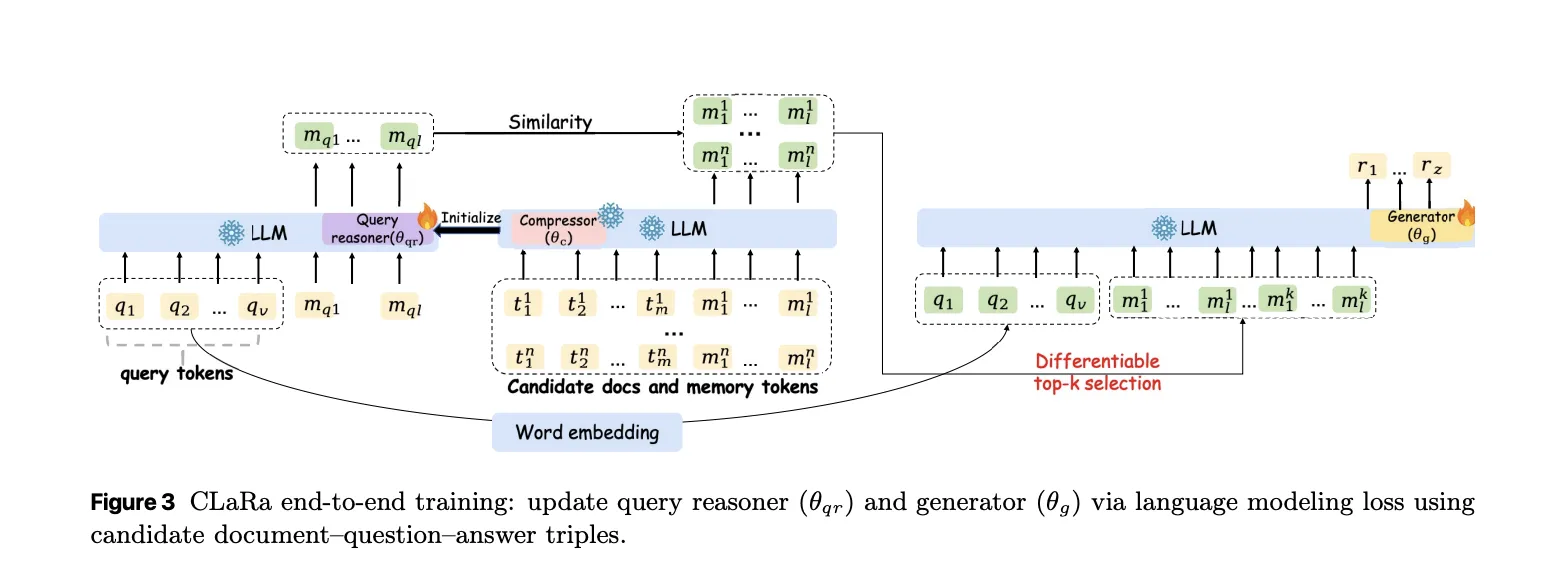

The introduces a neural long term memory module that is itself a deep multi layer perceptron rather than a vector or matrix state. Attention is interpreted as short term memory, since it only sees a limited window, while the neural memory acts as persistent long term memory.

For each token, Titans defines an associative memory loss

ℓ(Mₜ₋₁; kₜ, vₜ) = ‖Mₜ₋₁(kₜ) − vₜ‖²

where Mₜ₋₁ is the current memory, kₜ is the key and vₜ is the value. The gradient of this loss with respect to the memory parameters is the “surprise metric”. Large gradients correspond to surprising tokens that should be stored, small gradients correspond to expected tokens that can be mostly ignored.

The memory parameters are updated at test time by gradient descent with momentum and weight decay, which together act as a retention gate and forgetting mechanism.To keep this online optimization efficient, the research paper shows how to compute these updates with batched matrix multiplications over sequence chunks, which preserves parallel training across long sequences.

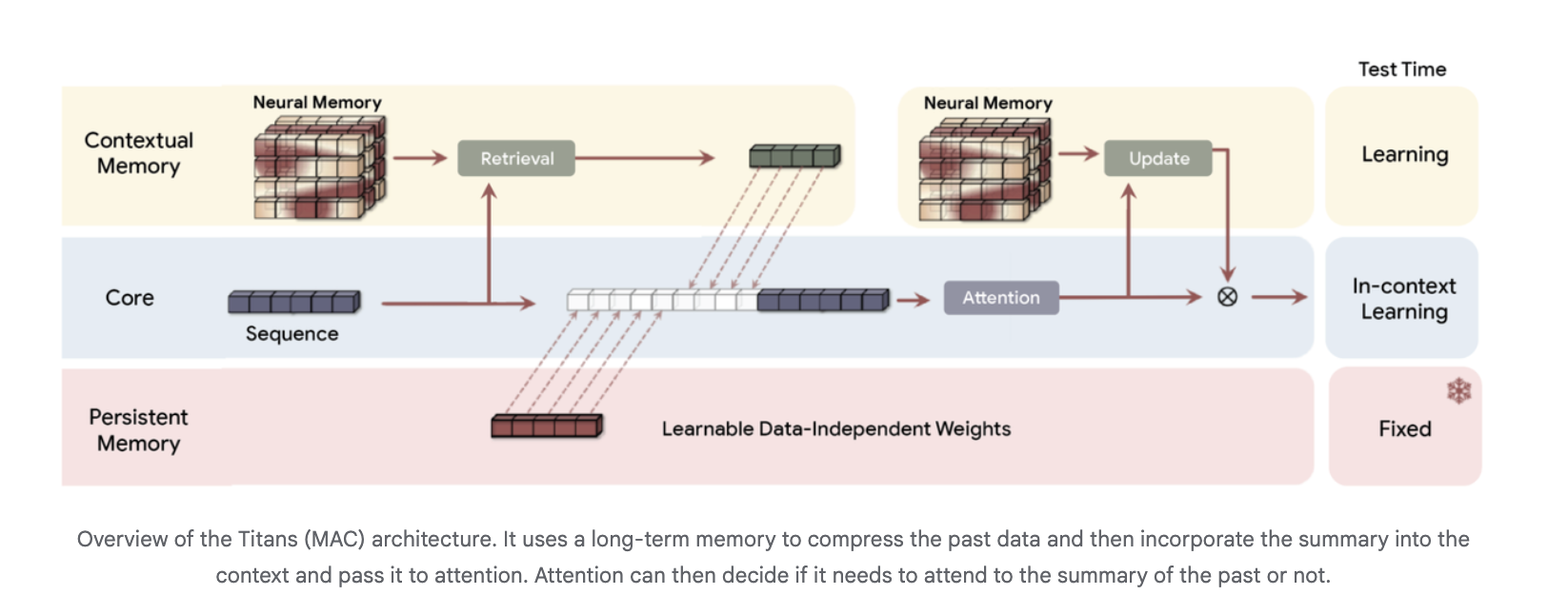

Architecturally, Titans uses three memory branches in the backbone, often instanced in the Titans MAC variant:

- a core branch that performs standard in context learning with attention

- a contextual memory branch that learns from the recent sequence

- a persistent memory branch with fixed weights that encodes pretraining knowledge

The long term memory compresses past tokens into a summary, which is then passed as extra context into attention. Attention can choose when to read that summary.

Experimental results for Titans

On language modeling and commonsense reasoning benchmarks such as C4, WikiText and HellaSwag, Titans architectures outperform state of the art linear recurrent baselines Mamba-2 and Gated DeltaNet and Transformer++ models of comparable size. The Google research attribute this to the higher expressive power of deep memory and its ability to maintain performance as context length grows. Deep neural memories with the same parameter budget but higher depth give consistently lower perplexity.

For extreme long context recall, the research team uses the BABILong benchmark, where facts are distributed across very long documents. Titans outperforms all baselines, including very large models such as GPT-4, while using many fewer parameters, and scales to context windows beyond 2,000,000 tokens.

The research team reports that Titans keeps efficient parallel training and fast linear inference. Neural memory alone is slightly slower than the fastest linear recurrent models, but hybrid Titans layers with Sliding Window Attention remain competitive on throughput while improving accuracy.

MIRAS, a unified framework for sequence models as associative memory

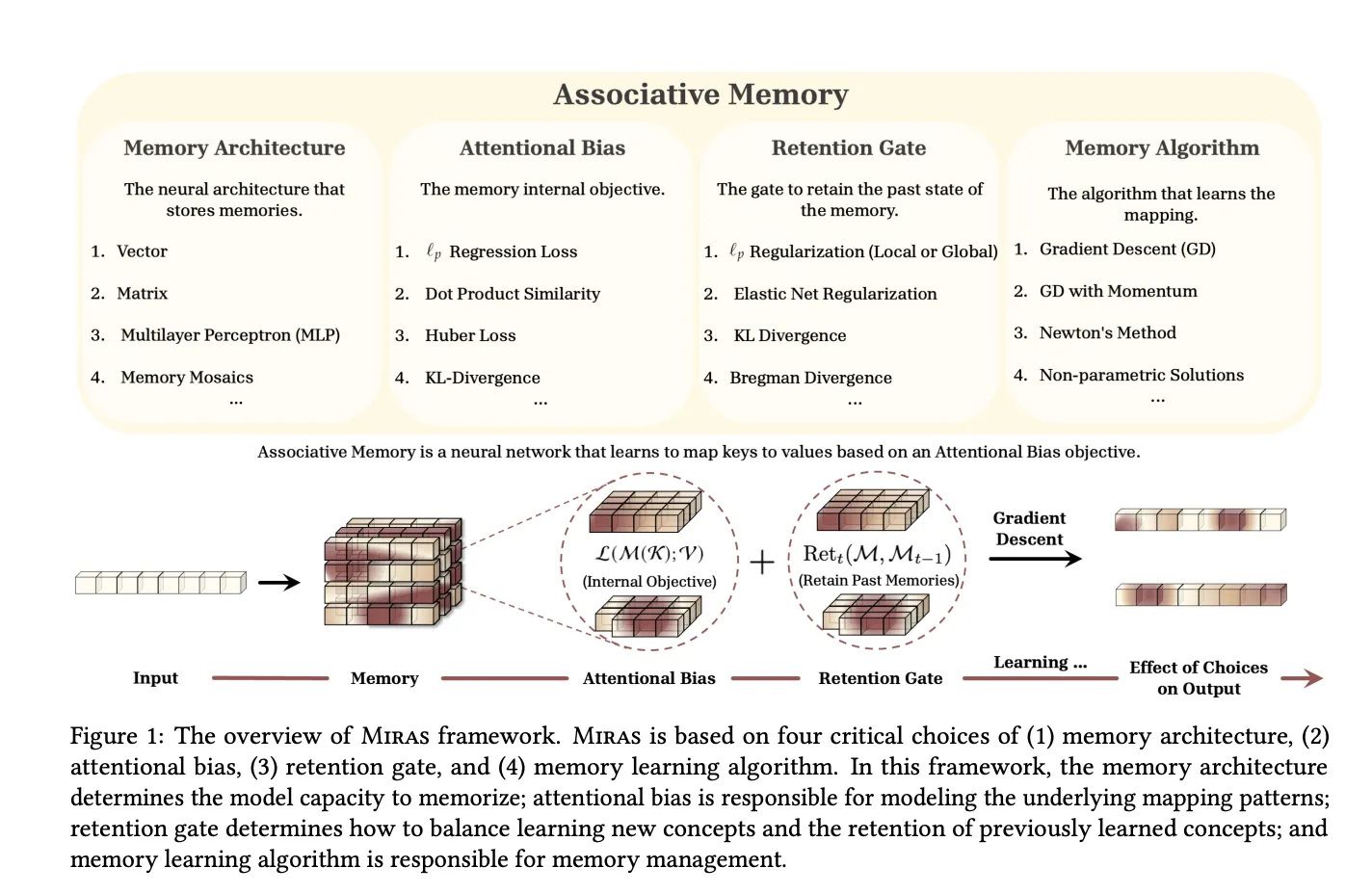

The MIRAS research paper, ,” generalizes this view. It observes that modern sequence models can be seen as associative memories that map keys to values while balancing learning and forgetting.

MIRAS defines any sequence model through four design choices:

- Memory structure for example a vector, linear map, or MLP

- Attentional bias the internal loss that defines what similarities the memory cares about

- Retention gate the regularizer that keeps the memory close to its past state

- Memory algorithm the online optimization rule, often gradient descent with momentum

Using this lens, MIRAS recovers several families:

- Hebbian style linear recurrent models and RetNet as dot product based associative memories

- Delta rule models such as DeltaNet and Gated DeltaNet as MSE based memories with value replacement and specific retention gates

- Titans LMM as a nonlinear MSE based memory with local and global retention optimized by gradient descent with momentum

Crucially, MIRAS then moves beyond the usual MSE or dot product objectives. The research team constructs new attentional biases based on Lₚ norms, robust Huber loss and robust optimization, and new retention gates based on divergences over probability simplices, elastic net regularization and Bregman divergence.

From this design space, the research team instantiate three attention free models:

- Moneta uses a 2 layer MLP memory with Lₚ attentional bias and a hybrid retention gate based on generalized norms

- Yaad uses the same MLP memory with Huber loss attentional bias and a forget gate related to Titans

- Memora uses regression loss as attentional bias and a KL divergence based retention gate over a probability simplex style memory.

These MIRAS variants replace attention blocks in a Llama style backbone, use depthwise separable convolutions in the Miras layer, and can be combined with Sliding Window Attention in hybrid models. Training remains parallel by chunking sequences and computing gradients with respect to the memory state from the previous chunk.

In research experiments, Moneta, Yaad and Memora match or surpass strong linear recurrent models and Transformer++ on language modeling, commonsense reasoning and recall intensive tasks, while maintaining linear time inference.

Key Takeaways

- Titans introduces a deep neural long term memory that learns at test time, using gradient descent on an L2 associative memory loss so the model selectively stores only surprising tokens while keeping updates parallelizable on accelerators.

- Titans combines attention with neural memory for long context, using branches like core, contextual memory and persistent memory so attention handles short range precision and the neural module maintains information over sequences beyond 2,000,000 tokens.

- Titans outperforms strong linear RNNs and Transformer++ baselines, including Mamba-2 and Gated DeltaNet, on language modeling and commonsense reasoning benchmarks at comparable parameter scales, while staying competitive on throughput.

- On extreme long context recall benchmarks such as BABILong, Titans achieves higher accuracy than all baselines, including larger attention models such as GPT 4, while using fewer parameters and still enabling efficient training and inference.

- MIRAS provides a unifying framework for sequence models as associative memories, defining them by memory structure, attentional bias, retention gate and optimization rule, and yields new attention free architectures such as Moneta, Yaad and Memora that match or surpass linear RNNs and Transformer++ on long context and reasoning tasks.

Check out the . Feel free to check out our . Also, feel free to follow us on and don’t forget to join our and Subscribe to . Wait! are you on telegram?

The post appeared first on .

META-REASONING:")

print(f" Complexity: {analysis.complexity}")

print(f" Strategy: {analysis.strategy.upper()}")

print(f" Confidence: {analysis.confidence:.2%}")

print(f" Reasoning: {analysis.reasoning}")

print(f"n

META-REASONING:")

print(f" Complexity: {analysis.complexity}")

print(f" Strategy: {analysis.strategy.upper()}")

print(f" Confidence: {analysis.confidence:.2%}")

print(f" Reasoning: {analysis.reasoning}")

print(f"n EXECUTING {analysis.strategy.upper()} STRATEGY...n")

if analysis.strategy == "fast":

resp = self.fast_engine.answer(query)

elif analysis.strategy == "cot":

resp = self.cot_engine.answer(query)

elif analysis.strategy == "tool":

if re.search(self.controller.patterns['math'], query.lower()):

resp = self.tool_executor.execute(query, "calculator")

else:

resp = self.tool_executor.execute(query, "search")

dt = time.time() - t0

analysis.execution_time = dt

self.stats[analysis.strategy]['count'] += 1

self.stats[analysis.strategy]['total_time'] += dt

self.controller.query_history.append(analysis)

if verbose:

print(resp)

print(f"n

EXECUTING {analysis.strategy.upper()} STRATEGY...n")

if analysis.strategy == "fast":

resp = self.fast_engine.answer(query)

elif analysis.strategy == "cot":

resp = self.cot_engine.answer(query)

elif analysis.strategy == "tool":

if re.search(self.controller.patterns['math'], query.lower()):

resp = self.tool_executor.execute(query, "calculator")

else:

resp = self.tool_executor.execute(query, "search")

dt = time.time() - t0

analysis.execution_time = dt

self.stats[analysis.strategy]['count'] += 1

self.stats[analysis.strategy]['total_time'] += dt

self.controller.query_history.append(analysis)

if verbose:

print(resp)

print(f"n Execution time: {dt:.4f}s")

return resp

def show_stats(self):

print("n" + "="*60)

print("AGENT PERFORMANCE STATISTICS")

print("="*60)

for s, d in self.stats.items():

if d['count'] > 0:

avg = d['total_time'] / d['count']

print(f"n{s.upper()} Strategy:")

print(f" Queries processed: {d['count']}")

print(f" Average time: {avg:.4f}s")

print("n" + "="*60)

Execution time: {dt:.4f}s")

return resp

def show_stats(self):

print("n" + "="*60)

print("AGENT PERFORMANCE STATISTICS")

print("="*60)

for s, d in self.stats.items():

if d['count'] > 0:

avg = d['total_time'] / d['count']

print(f"n{s.upper()} Strategy:")

print(f" Queries processed: {d['count']}")

print(f" Average time: {avg:.4f}s")

print("n" + "="*60)

Decomposing goal: {goal}")

agent_info = "n".join([f"- {name}: {agent.expertise}" for name, agent in self.agents.items()])

prompt = f"""Break down this goal into 3 specific subtasks. Assign each to the best agent.

Goal: {goal}

Available agents:

{agent_info}

Respond ONLY with a JSON array."""

response = self.llm.generate(prompt, max_tokens=250)

try:

json_match = re.search(r'[s*{.*?}s*]', response, re.DOTALL)

if json_match:

tasks_data = json.loads(json_match.group())

else:

raise ValueError("No JSON found")

except:

tasks_data = self._create_default_tasks(goal)

tasks = []

for i, task_data in enumerate(tasks_data[:3]):

task = Task(

id=task_data.get('id', f'task_{i+1}'),

description=task_data.get('description', f'Work on: {goal}'),

assigned_to=task_data.get('assigned_to', list(self.agents.keys())[i % len(self.agents)]),

dependencies=task_data.get('dependencies', [] if i == 0 else [f'task_{i}'])

)

self.tasks[task.id] = task

tasks.append(task)

self.log(f" ✓ {task.id}: {task.description[:50]}... → {task.assigned_to}")

return tasks

Decomposing goal: {goal}")

agent_info = "n".join([f"- {name}: {agent.expertise}" for name, agent in self.agents.items()])

prompt = f"""Break down this goal into 3 specific subtasks. Assign each to the best agent.

Goal: {goal}

Available agents:

{agent_info}

Respond ONLY with a JSON array."""

response = self.llm.generate(prompt, max_tokens=250)

try:

json_match = re.search(r'[s*{.*?}s*]', response, re.DOTALL)

if json_match:

tasks_data = json.loads(json_match.group())

else:

raise ValueError("No JSON found")

except:

tasks_data = self._create_default_tasks(goal)

tasks = []

for i, task_data in enumerate(tasks_data[:3]):

task = Task(

id=task_data.get('id', f'task_{i+1}'),

description=task_data.get('description', f'Work on: {goal}'),

assigned_to=task_data.get('assigned_to', list(self.agents.keys())[i % len(self.agents)]),

dependencies=task_data.get('dependencies', [] if i == 0 else [f'task_{i}'])

)

self.tasks[task.id] = task

tasks.append(task)

self.log(f" ✓ {task.id}: {task.description[:50]}... → {task.assigned_to}")

return tasks Executing {task.id} with {task.assigned_to}")

task.status = "in_progress"

agent = self.agents[task.assigned_to]

context_str = ""

if context and task.dependencies:

context_str = "nnContext from previous tasks:n"

for dep_id in task.dependencies:

if dep_id in context:

context_str += f"- {context[dep_id][:150]}...n"

prompt = f"""{agent.system_prompt}

Task: {task.description}{context_str}

Provide a clear, concise response:"""

result = self.llm.generate(prompt, max_tokens=250)

task.result = result

task.status = "completed"

self.log(f" ✓ Completed {task.id}")

return result

Executing {task.id} with {task.assigned_to}")

task.status = "in_progress"

agent = self.agents[task.assigned_to]

context_str = ""

if context and task.dependencies:

context_str = "nnContext from previous tasks:n"

for dep_id in task.dependencies:

if dep_id in context:

context_str += f"- {context[dep_id][:150]}...n"

prompt = f"""{agent.system_prompt}

Task: {task.description}{context_str}

Provide a clear, concise response:"""

result = self.llm.generate(prompt, max_tokens=250)

task.result = result

task.status = "completed"

self.log(f" ✓ Completed {task.id}")

return result Synthesizing final results")

results_text = "nn".join([f"Task {tid}:n{res[:200]}" for tid, res in results.items()])

prompt = f"""Combine these task results into one final coherent answer.

Original Goal: {goal}

Task Results:

{results_text}

Final comprehensive answer:"""

return self.llm.generate(prompt, max_tokens=350)

def execute_goal(self, goal: str) -> Dict[str, Any]:

self.log(f"n{'='*60}n

Synthesizing final results")

results_text = "nn".join([f"Task {tid}:n{res[:200]}" for tid, res in results.items()])

prompt = f"""Combine these task results into one final coherent answer.

Original Goal: {goal}

Task Results:

{results_text}

Final comprehensive answer:"""

return self.llm.generate(prompt, max_tokens=350)

def execute_goal(self, goal: str) -> Dict[str, Any]:

self.log(f"n{'='*60}n Starting Manager Agentn{'='*60}")

tasks = self.decompose_goal(goal)

results = {}

completed = set()

max_iterations = len(tasks) * 2

iteration = 0

while len(completed) < len(tasks) and iteration < max_iterations:

iteration += 1

for task in tasks:

if task.id in completed:

continue

deps_met = all(dep in completed for dep in task.dependencies)

if deps_met:

result = self.execute_task(task, results)

results[task.id] = result

completed.add(task.id)

final_output = self.synthesize_results(goal, results)

self.log(f"n{'='*60}n

Starting Manager Agentn{'='*60}")

tasks = self.decompose_goal(goal)

results = {}

completed = set()

max_iterations = len(tasks) * 2

iteration = 0

while len(completed) < len(tasks) and iteration < max_iterations:

iteration += 1

for task in tasks:

if task.id in completed:

continue

deps_met = all(dep in completed for dep in task.dependencies)

if deps_met:

result = self.execute_task(task, results)

results[task.id] = result

completed.add(task.id)

final_output = self.synthesize_results(goal, results)

self.log(f"n{'='*60}n Execution Complete!n{'='*60}n")

return {

"goal": goal,

"tasks": [asdict(task) for task in tasks],

"final_output": final_output,

"execution_log": self.execution_log

}

Execution Complete!n{'='*60}n")

return {

"goal": goal,

"tasks": [asdict(task) for task in tasks],

"final_output": final_output,

"execution_log": self.execution_log

} Try more:")

print(" - demo_coding()")

print(" - demo_custom('your goal here')")

Try more:")

print(" - demo_coding()")

print(" - demo_custom('your goal here')")